Animal-like Protists Are Commonly Called Algae

Animal-like Protists Are Commonly Called Algae

| Protist Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific nomenclature | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Groups included | |

| Supergroups [1] and typical phyla

Many others; | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

A protist () is whatever eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an creature, plant, or mucus. While it is likely that protists share a common antecedent (the final eukaryotic common antecedent), [2] the exclusion of other eukaryotes ways that protists do non course a natural group, or clade. [a] Therefore, some protists may exist more than closely related to animals, plants, or fungi than they are to other protists; however, like the groups algae , invertebrates , and protozoans , the biological category protist is used for convenience. Others classify whatsoever unicellular eukaryotic microorganism as a protist. [3] The study of protists is termed protistology. [four]

History [ edit ]

The classification of a third kingdom separate from animals and plants was first proposed by John Hogg in 1860 as the kingdom Protoctista; in 1866 Ernst Haeckel besides proposed a third kingdom Protista as "the kingdom of primitive forms". [5] Originally these too included prokaryotes, just with time[ when? ] these were removed to a fourth kingdom Monera. [b]

In the pop v-kingdom scheme proposed past Robert Whittaker in 1969, Protista was defined equally eukaryotic "organisms which are unicellular or unicellular-colonial and which grade no tissues", and the fifth kingdom Fungi was established. [six] [seven] [c] In the v-kingdom system of Lynn Margulis, the term protist is reserved for microscopic organisms, while the more than inclusive kingdom Protoctista (or protoctists) included sure large multicellular eukaryotes, such every bit kelp, red algae, and slime molds. [10] Some use the term protist interchangeably with Margulis's protoctist, to cover both single-celled and multicellular eukaryotes, including those that form specialized tissues only do not fit into any of the other traditional kingdoms. [11]

Clarification [ edit ]

As well their relatively simple levels of organization, protists do non necessarily have much in common. [12] When used, the term "protists" is now considered to mean a paraphyletic assemblage of similar-appearing but diverse taxa (biological groups); these taxa do not accept an exclusive common ancestor beyond being equanimous of eukaryotes, and have different life cycles, trophic levels, modes of locomotion, and cellular structures. [13] [14]

Examples of protists include: [15]

- Amoebas (including nucleariids and Foraminifera);

- choanaflagellates; ciliates;

- Diatoms;

- Dinoflagellates;

- Giardia ;

- Plasmodium (which causes malaria);

- Oomycetes (including Phytophthora , the cause of the Peachy Famine of Ireland); and

- slime molds.

These examples are unicellular, although oomycetes tin bring together to form filaments, and slime molds can aggregate into a tissue-like mass.

In cladistic systems (classifications based on common beginnings), there are no equivalents to the taxa Protista or Protoctista, as both terms refer to a paraphyletic group that spans the entire eukaryotic branch of the tree of life. In cladistic classification, the contents of Protista are mostly distributed amidst various supergroups: examples include the

- SAR supergroup (of stramenopiles or heterokonts, alveolates, and Rhizaria);

- Archaeplastida (or Plantae sensu lato );

- Excavata (which is more often than not unicellular flagellates); and

- Opisthokonta (which ordinarily includes unicellular flagellates, but as well animals and fungi).

"Protista", "Protoctista", and "Protozoa" are therefore considered obsolete. However, the term "protist" continues to be used informally as a catch-all term for eukaryotic organisms that are not inside other traditional kingdoms. For instance, the word "protist pathogen" may be used to denote any affliction-causing organism that is not plant, animal, fungal, prokaryotic, viral, or subviral. [16]

Subdivisions [ edit ]

The term Protista was first used by Ernst Haeckel in 1866. Protists were traditionally subdivided into several groups based on similarities to the "higher" kingdoms such as: [v]

- Protozoa

- Protozoans are unicellular "brute-like" (heterotrophic, and sometimes parasitic) organisms that are further sub-divided based on characteristics such every bit move, such as the (flagellated) Flagellata, the (ciliated) Ciliophora, the (phagocytic) amoeba, and the (spore-forming) Sporozoa.

- Protophyta

- Protophyta are "plant-like" (autotrophic) organisms that are composed mostly of unicellular algae. The dinoflagellates, diatoms and Euglena-like flagellates are photosynthetic protists.

- Mold

- Molds generally refer to fungi; but slime molds and water molds are "fungus-like" (saprophytic) protists, although some are pathogens. Two separate types of slime molds exist, the cellular and acellular forms.

Some protists, sometimes chosen ambiregnal protists, take been considered to be both protozoa and algae or fungi (e.g., slime molds and flagellated algae), and names for these have been published nether either or both of the ICN and the ICZN . [17] [18] Conflicts, such equally these – for example the dual-classification of Euglenids and Dinobryons, which are mixotrophic – is an example of why the kingdom Protista was adopted.

These traditional subdivisions, largely based on superficial commonalities, have been replaced by classifications based on phylogenetics (evolutionary relatedness amid organisms). Molecular analyses in modernistic taxonomy have been used to redistribute onetime members of this group into diverse and sometimes distantly related phyla. For example, the h2o molds are at present considered to exist closely related to photosynthetic organisms such as Brownish algae and Diatoms, the slime molds are grouped mainly under Amoebozoa, and the Amoebozoa itself includes only a subset of the "Amoeba" group, and significant number of erstwhile "Amoeboid" genera are distributed among Rhizarians and other Phyla.

However, the older terms are still used every bit informal names to describe the morphology and ecology of various protists. For example, the term protozoa is used to refer to heterotrophic species of protists that do not course filaments.

Classification [ edit ]

Historical classifications [ edit ]

Among the pioneers in the study of the protists, which were well-nigh ignored by Linnaeus except for some genera (e.yard., Vorticella, Anarchy, Volvox, Corallina, Conferva, Ulva, Chara, Fucus ) [19] [20] were Leeuwenhoek, O. F. Müller, C. Thousand. Ehrenberg and Félix Dujardin. [21] The start groups used to classify microscopic organism were the Animalcules and the Infusoria. [22] In 1818, the German naturalist Georg August Goldfuss introduced the word Protozoa to refer to organisms such as ciliates and corals. [23] [5] After the cell theory of Schwann and Schleiden (1838–39), this group was modified in 1848 past Carl von Siebold to include only animal-like unicellular organisms, such as foraminifera and amoebae. [24] The formal taxonomic category Protoctista was first proposed in the early 1860s by John Hogg, who argued that the protists should include what he saw equally primitive unicellular forms of both plants and animals. He defined the Protoctista as a "fourth kingdom of nature", in addition to the then-traditional kingdoms of plants, animals and minerals. [25] [5] The kingdom of minerals was later removed from taxonomy in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel, leaving plants, animals, and the protists (Protista), defined as a "kingdom of primitive forms". [26] [27]

In 1938, Herbert Copeland resurrected Hogg's label, arguing that Haeckel'southward term Protista included anucleated microbes such as leaner, which the term "Protoctista" (literally significant "get-go established beings") did not. In contrast, Copeland's term included nucleated eukaryotes such as diatoms, green algae and fungi. [28] This classification was the footing for Whittaker's later definition of Fungi, Animalia, Plantae and Protista as the 4 kingdoms of life. [8] The kingdom Protista was later modified to separate prokaryotes into the separate kingdom of Monera, leaving the protists as a group of eukaryotic microorganisms. [half-dozen] These five kingdoms remained the accustomed classification until the development of molecular phylogenetics in the late 20th century, when it became apparent that neither protists nor monera were single groups of related organisms (they were not monophyletic groups). [29]

Modern classifications [ edit ]

Systematists today practice not care for Protista as a formal taxon, simply the term "protist" is still commonly used for convenience in ii means. [thirty] The most popular contemporary definition is a phylogenetic i, that identifies a paraphyletic group: [31] a protist is any eukaryote that is not an animal, (land) plant, or (true) mucus; this definition [32] excludes many unicellular groups, like the Microsporidia (fungi), many Chytridiomycetes (fungi), and yeasts (fungi), and also a non-unicellular group included in Protista in the past, the Myxozoa (beast). [33] Some systematists[ who? ] judge paraphyletic taxa acceptable, and utilize Protista in this sense every bit a formal taxon (equally plant in some secondary textbooks, for pedagogical purpose).[ citation needed ]

The other definition describes protists primarily by functional or biological criteria: protists are essentially those eukaryotes that are never multicellular, [30] that either exist as independent cells, or if they occur in colonies, practise not show differentiation into tissues (just vegetative cell differentiation may occur restricted to sexual reproduction, alternate vegetative morphology, and quiescent or resistant stages, such as cysts); [34] this definition excludes many dark-brown, multicellular red and green algae, which may accept tissues.

The taxonomy of protists is however changing. Newer classifications attempt to present monophyletic groups based on morphological (especially ultrastructural), [35] [36] [37] biochemical (chemotaxonomy) [38] [39] and Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence (molecular research) information. [40] [41] All the same, there are sometimes discordances between molecular and morphological investigations; these tin can exist categorized every bit two types: (i) one morphology, multiple lineages (e.m. morphological convergence, ambiguous species) and (2) one lineage, multiple morphologies (e.one thousand. phenotypic plasticity, multiple life-wheel stages). [42]

Because the protists as a whole are paraphyletic, new systems often dissever or abandon the kingdom, instead treating the protist groups as separate lines of eukaryotes. The contempo scheme past Adl et al. (2005) [34] does not recognize formal ranks (phylum, class, etc.) and instead treats groups as clades of phylogenetically related organisms. This is intended to brand the classification more stable in the long term and easier to update. Some of the primary groups of protists, which may be treated equally phyla, are listed in the taxobox, upper correct. [43] Many are thought to be monophyletic, though there is however uncertainty. For example, the Excavata are probably not monophyletic and the chromalveolates are probably only monophyletic if the haptophytes and cryptomonads are excluded. [44]

In 2015 a Higher Level Classification of all Living Organisms was arrived at past consensus with many authors including Cavalier-Smith. This classification proposes ii superkingdoms and vii kingdoms. The superkingdoms are those of Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes. The Prokaryotes include ii kingdoms of Bacteria and Archaea; the Eukaryotes include 5 kingdoms of Protozoa, Chromista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia. The scheme retains fourteen taxonomic ranks. Eukaryotic unicellular organisms are referred to as protists. [45]

Metabolism [ edit ]

Nutrition can vary according to the blazon of protist. Most eukaryotic algae are autotrophic, but the pigments were lost in some groups.[ vague ] Other protists are heterotrophic, and may present phagotrophy, osmotrophy, saprotrophy or parasitism. Some are mixotrophic. Some protists that do non have / lost chloroplasts/mitochondria have entered into endosymbiontic human relationship with other bacteria/algae to replace the missing functionality. For example, Paramecium bursaria and Paulinella accept captured a green alga ( Zoochlorella ) and a cyanobacterium respectively that act equally replacements for chloroplast. Meanwhile, a protist, Mixotricha paradoxa that has lost its mitochondria uses endosymbiontic bacteria as mitochondria and ectosymbiontic hair-like bacteria ( Treponema spirochetes ) for locomotion.

Many protists are flagellate, for example, and filter feeding can take place where flagellates discover prey. Other protists tin engulf leaner and other food particles, past extending their jail cell membrane around them to form a food vacuole and digesting them internally in a process termed phagocytosis.

| Nutritional type | Source of energy | Source of carbon | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoautotrophs | Sunlight | Organic compounds or carbon fixation | Virtually algae |

| Chemoheterotrophs | Organic compounds | Organic compounds | Apicomplexa, Trypanosomes or Amoebae |

For well-nigh important cellular structures and functions of fauna and plants, it can be found a heritage amidst protists. [46]

Reproduction [ edit ]

Some protists reproduce sexually using gametes, while others reproduce asexually by binary fission.

Some species, for example Plasmodium falciparum , have extremely circuitous life cycles that involve multiple forms of the organism, some of which reproduce sexually and others asexually. [47] However, information technology is unclear how frequently sexual reproduction causes genetic commutation between different strains of Plasmodium in nature and well-nigh populations of parasitic protists may be clonal lines that rarely exchange genes with other members of their species. [48]

Eukaryotes emerged in evolution more than 1.five billion years ago. [49] The primeval eukaryotes were likely protists. Although sexual reproduction is widespread amidst extant eukaryotes, it seemed unlikely until recently, that sex could be a primordial and cardinal characteristic of eukaryotes. A main reason for this view was that sex appeared to be lacking in certain pathogenic protists whose ancestors branched off early from the eukaryotic family unit tree. However, several of these protists are now known to be capable of, or to recently accept had the adequacy for, meiosis and hence sexual reproduction. For example, the common intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia was once considered to be a descendant of a protist lineage that predated the emergence of meiosis and sex. However, G. lamblia was recently found to have a core prepare of genes that function in meiosis and that are widely present among sexual eukaryotes. [50] These results suggested that Thousand. lamblia is capable of meiosis and thus sexual reproduction. Furthermore, straight testify for meiotic recombination, indicative of sex, was likewise found in G. lamblia. [51]

The pathogenic parasitic protists of the genus Leishmania have been shown to be capable of a sexual bike in the invertebrate vector, likened to the meiosis undertaken in the trypanosomes. [52]

Trichomonas vaginalis , a parasitic protist, is not known to undergo meiosis, but when Malik et al. [53] tested for 29 genes that role in meiosis, they constitute 27 to be present, including eight of 9 genes specific to meiosis in model eukaryotes. These findings advise that T. vaginalis may exist capable of meiosis. Since 21 of the 29 meiotic genes were also nowadays in Chiliad. lamblia, information technology appears that about of these meiotic genes were likely present in a common ancestor of T. vaginalis and G. lamblia. These two species are descendants of protist lineages that are highly divergent among eukaryotes, leading Malik et al. [53] to suggest that these meiotic genes were likely present in a mutual antecedent of all eukaryotes.

Based on a phylogenetic analysis, Dacks and Roger proposed that facultative sexual activity was present in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes. [54]

This view was further supported by a study of amoebae by Lahr et al. [55] Amoeba take by and large been regarded as asexual protists. Withal, these authors describe evidence that most amoeboid lineages are anciently sexual, and that the majority of asexual groups likely arose recently and independently. Early researchers (eastward.thou., Calkins) have interpreted phenomena related to chromidia (chromatin granules free in the cytoplasm) in amoeboid organisms as sexual reproduction. [56]

Protists more often than not reproduce asexually under favorable environmental weather, but tend to reproduce sexually under stressful weather condition, such equally starvation or estrus shock. [57] Oxidative stress, which is associated with the production of reactive oxygen species leading to DNA damage, also appears to be an important factor in the consecration of sex in protists. [57]

Some commonly found Protist pathogens such as Toxoplasma gondii are capable of infecting and undergoing asexual reproduction in a wide variety of animals – which act as secondary or intermediate host – but can undergo sexual reproduction only in the master or definitive host (for case: felids such every bit domestic cats in this case). [58] [59] [60]

Ecology [ edit ]

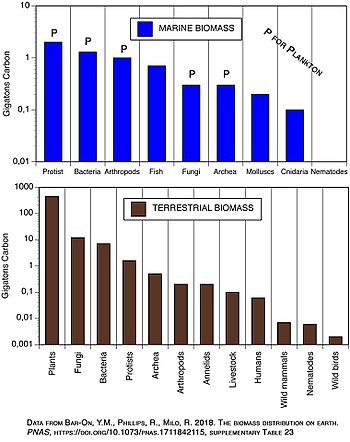

Free-living Protists occupy nearly any environment that contains liquid water. Many protists, such every bit algae, are photosynthetic and are vital principal producers in ecosystems, especially in the ocean as office of the plankton. Protists brand upwards a large portion of the biomass in both marine and terrestrial environments. [61]

Other protists include pathogenic species, such as the kinetoplastid Trypanosoma brucei , which causes sleeping sickness, and species of the apicomplexan Plasmodium , which crusade malaria.

Parasitism: role every bit pathogens [ edit ]

Some protists are significant parasites of animals (e.chiliad.; five species of the parasitic genus Plasmodium cause malaria in humans and many others cause similar diseases in other vertebrates), plants [62] [63] (the oomycete Phytophthora infestans causes late bane in potatoes) [64] or even of other protists. [65] [66] Protist pathogens share many metabolic pathways with their eukaryotic hosts. This makes therapeutic target evolution extremely difficult – a drug that harms a protist parasite is also probable to impairment its animal/plant host. A more thorough understanding of protist biological science may allow these diseases to be treated more efficiently. For example, the apicoplast (a nonphotosynthetic chloroplast only essential to acquit out important functions other than photosynthesis) present in apicomplexans provides an bonny target for treating diseases caused by dangerous pathogens such as plasmodium.

Recent papers have proposed the use of viruses to treat infections acquired by protozoa. [67] [68]

Researchers from the Agricultural Research Service are taking advantage of protists as pathogens to control red imported burn ant ( Solenopsis invicta ) populations in Argentine republic. Spore-producing protists such as Kneallhazia solenopsae (recognized every bit a sister clade or the closest relative to the fungus kingdom now) [69] can reduce blood-red burn down emmet populations past 53–100%. [70] Researchers accept also been able to infect phorid fly parasitoids of the ant with the protist without harming the flies. This turns the flies into a vector that tin can spread the pathogenic protist between cherry-red fire ant colonies. [71]

Fossil record [ edit ]

Many protists have neither hard parts nor resistant spores, and their fossils are extremely rare or unknown. Examples of such groups include the apicomplexans, [72] most ciliates, [73] some green algae (the Klebsormidiales), [74] choanoflagellates, [75] oomycetes, [76] brown algae, [77] yellow-green algae, [78] Excavata (e.yard., euglenids). [79] Some of these accept been plant preserved in amber (fossilized tree resin) or nether unusual weather (e.g., Paleoleishmania , a kinetoplastid).

Others are relatively common in the fossil record, [fourscore] as the diatoms, [81] gilt algae, [82] haptophytes (coccoliths), [83] silicoflagellates, tintinnids (ciliates), dinoflagellates, [84] green algae, [85] red algae, [86] heliozoans, radiolarians, [87] foraminiferans, [88] ebriids and testate amoebae (euglyphids, arcellaceans). [89] Some are fifty-fifty used as paleoecological indicators to reconstruct ancient environments.

More probable eukaryote fossils begin to appear at well-nigh 1.viii billion years ago, the acritarchs, spherical fossils of probable algal protists. [ninety] Another possible representative of early fossil eukaryotes are the Gabonionta.

See also [ edit ]

Footnotes [ edit ]

- ^ a b The get-go eukaryotes were "neither plants, animals, nor fungi", hence as defined, the category protist would include the last eukaryotic common antecedent.

- ^ Monera eventually became the two domains Bacteria and Archaea . [5]

- ^ In the original 4-kingdom model proposed in 1959, Protista included all unicellular microorganisms such as bacteria. Herbert Copeland proposed separate kingdoms, Mychota for prokaryotes and Protoctista for eukaryotes (including fungi) that were neither plants nor animals. Copeland's distinction between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells was eventually critical in Whittaker proposing a terminal v-kingdom organisation, even though he resisted it for over a decade. [viii] [9]

References [ edit ]

- ^ Adl SM, Simpson AG, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Bass D, Bowser SS, Chocolate-brown MW, Burki F, Dunthorn M, Hampl V, Heiss A, Hoppenrath M, Lara E, Le Gall 50, Lynn DH, McManus H, Mitchell EA, Mozley-Stanridge SE, Earnest H, Aurther T, Parfrey LW, Pawlowski J, Rueckert S, Shadwick Fifty, Shadwick Fifty, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Spiegel FW (September 2012). "The revised classification of eukaryotes" (PDF). The Periodical of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 59 (5): 429–493. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.10. PMC 3483872 . PMID23020233.

- ^ O'Malley, Maureen A.; Leger, Michelle M.; Wideman, Jeremy 1000.; Ruiz-Trillo, Iñaki (2022-02-eighteen). "Concepts of the last eukaryotic mutual ancestor". Nature Environmental & Evolution. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 3 (iii): 338–344. doi:ten.1038/s41559-019-0796-3. hdl: 10261/201794 . ISSN2397-334X. PMID30778187. S2CID67790751.

- ^ Madigan, Michael T. (2022). Brock biology of microorganisms (Fifteenth, Global ed.). NY, NY. p. 594. ISBN 9781292235103 .

- ^ Taylor, F.J.R.M. (2003-xi-01). "The collapse of the two-kingdom system, the ascent of protistology and the founding of the International Society for Evolutionary Protistology (ISEP)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. Microbiology Society. 53 (half dozen): 1707–1714. doi: x.1099/ijs.0.02587-0 . ISSN1466-5026. PMID14657097.

- ^ a b c d east Scamardella JM (1999). "Not plants or animals: A brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista, and Protoctista" (PDF). International Microbiology. 2 (four): 207–221. PMID10943416.

- ^ a b Whittaker RH (Jan 1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science. 163 (3863): 150–160. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..150W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.5430 . doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID5762760.

- ^ "whittaker new concepts of kingdoms – Google Scholar". scholar.google.ca . Retrieved 2016-02-28 .

- ^ a b Whittaker RH (1959). "On the Broad Classification of Organisms". Quarterly Review of Biology. 34 (3): 210–226. doi:10.1086/402733. JSTOR2816520. PMID13844483. S2CID28836075.

- ^ Hagen JB (2012). "depiction of Whittaker's early on iv-kingdom system, based on three modes of diet and the distinction between unicellular and multicellular trunk plans". BioScience. 62: 67–74. doi: 10.1525/bio.2012.62.1.11 .

- ^ Margulis L, Chapman MJ (2009-03-xix). Kingdoms and Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on World . Academic Press. ISBN 9780080920146 .

- ^ Archibald, John M.; Simpson, Alastair K. B.; Slamovits, Claudio H., eds. (2017). Handbook of the Protists (ii ed.). Springer International Publishing. pp. ix. ISBN 978-3-319-28147-6 .

- ^ "Systematics of the Eukaryota" . Retrieved 2009-05-31 .

- ^ Simonite T (Nov 2005). "Protists push button animals aside in rule revamp". Nature. 438 (7064): 8–9. Bibcode:2005Natur.438....8S. doi: 10.1038/438008b . PMID16267517.

- ^ Harper D, Benton, Michael (2009). Introduction to Paleobiology and the Fossil Record . Wiley-Blackwell. p.207. ISBN 978-1-4051-4157-4 .

- ^ "Protists". basicbiology.cyberspace. basicbiology.net.

- ^ Siddiqui R, Kulsoom H, Lalani S, Khan NA (July 2016). "Isolation of Balamuthia mandrillaris-specific antibiotic fragments from a bacteriophage antibody brandish library". Experimental Parasitology. 166: 94–96. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2016.04.001. PMID27055361.

- ^ Corliss, J.O. (1995). "The ambiregnal protists and the codes of nomenclature: a cursory review of the problem and of proposed solutions". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 52: 11–17. doi: ten.5962/bhl.part.6717 .

- ^ Barnes, Richard Stephen Kent (2001). The Invertebrates: A Synthesis. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 41. ISBN978-0-632-04761-1.

- ^ Ratcliff, Marc J. (2009). "The Emergence of the Systematics of Infusoria". In: The Quest for the Invisible: Microscopy in the Enlightenment. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- ^ Sharma, O.P. (1986). Textbook of Algae . McGraw Hill. p. 22. ISBN 9780074519288 – via Google Books.

- ^ Fauré-Frémiet, E. & Théodoridès, J. (1972). État des connaissances sur la structure des Protozoaires avant la formulation de la Théorie cellulaire. Revue d'histoire des sciences, 27–44.

- ^ The Flagellates. Unity, diverseness and evolution. Ed.: Barry S. C. Leadbeater and J. C. Green Taylor and Francis, London 2000, p. 3.

- ^ Goldfuß (1818). "Ueber die Nomenclature der Zoophyten" [On the classification of zoophytes]. Isis, Oder, Encyclopädische Zeitung von Oken (in German). 2 (vi): 1008–1019. From p. 1008: "Erste Klasse. Urthiere. Protozoa." (Kickoff class. Primordial animals. Protozoa.) [Note: each column of each folio of this journal is numbered; at that place are two columns per page.]

- ^ Siebold (vol. i); Stannius (vol. two) (1848). Lehrbuch der vergleichenden Anatomie [Textbook of Comparative Anatomy] (in German language). Vol. i: Wirbellose Thiere (Invertebrate animals). Berlin, (Frg): Veit & Co. p. three. From p. 3: "Erste Hauptgruppe. Protozoa. Thiere, in welchen dice verschiedenen Systeme der Organe nicht scharf ausgeschieden sind, und deren unregelmässige Course und einfache Organisation sich auf eine Zelle reduziren lassen." (First principal group. Protozoa. Animals, in which the unlike systems of organs are non sharply separated, and whose irregular form and simple organization can exist reduced to one cell.)

- ^ Hogg, John (1860). "On the distinctions of a plant and an animate being, and on a 4th kingdom of nature". Edinburgh New Philosophical Periodical. 2nd series. 12: 216–225. From p. 223: "... I here suggest a 4th or an boosted kingdom, under the title of the Primigenal kingdom, ... This Primigenal kingdom would comprise all the lower creatures, or the primary organic beings, – 'Protoctista,' – from πρώτος, starting time, and χτιστά, created beings; ..."

- ^ Rothschild LJ (1989). "Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: what's in a name?". Journal of the History of Biology. 22 (2): 277–305. doi:10.1007/BF00139515. PMID11542176. S2CID32462158.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1866). Generelle Morphologie der Organismen [The General Morphology of Organisms] (in German). Vol. ane. Berlin, (Germany): G. Reimer. pp. 215ff. From p. 215: "7. Character des Protistenreiches." (VII. Character of the kingdom of Protists.)

- ^ Copeland HF (1938). "The Kingdoms of Organisms". Quarterly Review of Biology. 13 (four): 383–420. doi:10.1086/394568. JSTOR2808554. S2CID84634277.

- ^ Stechmann A, Cavalier-Smith T (September 2003). "The root of the eukaryote tree pinpointed" (PDF). Electric current Biological science. 13 (17): R665–667. doi: ten.1016/S0960-9822(03)00602-X . PMID12956967. S2CID6702524.

- ^ a b O'Malley MA, Simpson AG, Roger AJ (2012). "The other eukaryotes in light of evolutionary protistology". Biology & Philosophy. 28 (two): 299–330. doi:ten.1007/s10539-012-9354-y. S2CID85406712.

- ^ Schlegel, M.; Hulsmann, N. (2007). "Protists – A textbook instance for a paraphyletic taxon☆". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 7 (two): 166–172. doi:ten.1016/j.ode.2006.11.001.

- ^ "Protista". microbeworld.org. Archived from the original on 13 June 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ Štolc A (1899). "Actinomyxidies, nouveau groupe de Mesozoaires parent des Myxosporidies". Bull. Int. l'Acad. Sci. Bohème. 12: one–12.

- ^ a b Adl SM, Simpson AG, Farmer MA, Andersen RA, Anderson OR, Barta JR, Bowser SS, Brugerolle G, Fensome RA, Fredericq S, James TY, Karpov S, Kugrens P, Krug J, Lane CE, Lewis LA, Gild J, Lynn DH, Isle of mann DG, McCourt RM, Mendoza L, Moestrup O, Mozley-Standridge SE, Nerad TA, Shearer CA, Smirnov AV, Spiegel FW, Taylor MF (2005). "The new college level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 52 (5): 399–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x . PMID16248873. S2CID8060916.

- ^ Pitelka, D. R. (1963). Electron-Microscopic Structure of Protozoa . Pergamon Press, Oxford.

- ^ Berner, T. (1993). Ultrastructure of Microalgae . Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN0849363233

- ^ Beckett, A., Heath, I. B., and Mclaughlin, D. J. (1974). An Atlas of Fungal Ultrastructure. Longman, Dark-green, New York.

- ^ Ragan 1000.A. & Chapman D.J. (1978). A Biochemical Phylogeny of the Protists. London, New York: Academic Press. ISBN0323155618

- ^ Lewin R. A. (1974). "Biochemical taxonomy", pp. 1–39 in Algal Physiology and Biochemistry , Stewart W. D. P. (ed.). Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford. ISBN0520024109

- ^ Oren, A., & Papke, R. T. (2010). Molecular phylogeny of microorganisms . Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press. ISBN1904455670

- ^ Horner, D. S., & Hirt, R. P. (2004). "An overview on eukaryote origins and development: the beauty of the cell and the fabulous gene phylogenies", pp. 1–26 in Hirt, R.P. & D.S. Horner. Organelles, Genomes and Eukaryote Phylogeny, An Evolutionary Synthesis in the Age of Genomics. New York: CRC Press. ISBN0203508939

- ^ Lahr DJ, Laughinghouse Hd, Oliverio AM, Gao F, Katz LA (October 2014). "How discordant morphological and molecular evolution amid microorganisms can revise our notions of biodiversity on Earth". BioEssays. 36 (10): 950–959. doi:10.1002/bies.201400056. PMC 4288574 . PMID25156897.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE (October 2003). "Phylogeny and classification of phylum Cercozoa (Protozoa)". Protist. 154 (3–4): 341–358. doi:x.1078/143446103322454112. PMID14658494.

- ^ Parfrey LW, Barbero E, Lasser E, Dunthorn M, Bhattacharya D, Patterson DJ, Katz LA (December 2006). "Evaluating support for the current nomenclature of eukaryotic diverseness". PLOS Genetics. two (12): e220. doi:x.1371/journal.pgen.0020220. PMC 1713255 . PMID17194223.

- ^ Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Condescending-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D.; Kirk, Paul M.; Thuesen, Erik V. (2015). "A higher level classification of all living organisms". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi: x.1371/journal.pone.0119248 . PMC 4418965 . PMID25923521.

- ^ Plattner H (2022). "Evolutionary cell biology of proteins from protists to humans and plants". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 65 (ii): 255–289. doi:10.1111/jeu.12449. PMID28719054. S2CID206055044.

- ^ Talman AM, Domarle O, McKenzie FE, Ariey F, Robert Five (July 2004). "Gametocytogenesis: the puberty of Plasmodium falciparum". Malaria Journal. 3: 24. doi:x.1186/1475-2875-3-24. PMC 497046 . PMID15253774.

- ^ Tibayrenc K, et al. (June 1991). "Are eukaryotic microorganisms clonal or sexual? A population genetics vantage". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the U.s.a. of America. 88 (12): 5129–33. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.5129T. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5129 . PMC 51825 . PMID1675793.

- ^ Javaux EJ, Knoll AH, Walter MR (July 2001). "Morphological and ecological complexity in early eukaryotic ecosystems". Nature. 412 (6842): 66–69. Bibcode:2001Natur.412...66J. doi:10.1038/35083562. PMID11452306. S2CID205018792.

- ^ Ramesh MA, Malik SB, Logsdon JM (January 2005). "A phylogenomic inventory of meiotic genes; evidence for sex in Giardia and an early eukaryotic origin of meiosis". Electric current Biology. 15 (2): 185–191. doi: ten.1016/j.cub.2005.01.003 . PMID15668177. S2CID17013247.

- ^ Cooper MA, Adam RD, Worobey Chiliad, Sterling CR (Nov 2007). "Population genetics provides evidence for recombination in Giardia". Current Biology. 17 (22): 1984–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.020 . PMID17980591. S2CID15991722.

- ^ Akopyants NS, et al. (April 2009). "Demonstration of genetic commutation during cyclical development of Leishmania in the sand fly vector". Scientific discipline. 324 (5924): 265–268. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..265A. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.1169464. PMC 2729066 . PMID19359589.

- ^ a b Malik SB, Pightling AW, Stefaniak LM, Schurko AM, Logsdon JM (August 2007). Hahn MW (ed.). "An expanded inventory of conserved meiotic genes provides bear witness for sexual activity in Trichomonas vaginalis". PLOS One. 3 (8): e2879. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2879M. doi: x.1371/journal.pone.0002879 . PMC 2488364 . PMID18663385.

- ^ Dacks J, Roger AJ (June 1999). "The first sexual lineage and the relevance of facultative sexual activity". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 48 (6): 779–783. Bibcode:1999JMolE..48..779D. doi:ten.1007/PL00013156. PMID10229582. S2CID9441768.

- ^ Lahr DJ, Parfrey LW, Mitchell EA, Katz LA, Lara E (July 2011). "The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating show for sex activity in amoeboid organisms". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 278 (1715): 2081–2090. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0289. PMC 3107637 . PMID21429931.

- ^ Dobell, C. (1909). "Chromidia and the binuclearity hypotheses: A review and a criticism" (PDF). Quarterly Periodical of Microscopical Science. 53: 279–326.

- ^ a b Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Michod RE (2012). "DNA repair as the primary adaptive part of sex in bacteria and eukaryotes". Chapter i: pp. one–49 in Deoxyribonucleic acid Repair: New Research, Sakura Kimura and Sora Shimizu (eds.). Nova Sci. Publ., Hauppauge, Due north.Y. ISBN978-i-62100-808-8

- ^ "CDC – Toxoplasmosis – Biology". 17 March 2015. Retrieved fourteen June 2015.

- ^ "Cat parasite linked to mental affliction, schizophrenia". CBS. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "CDC – About Parasites" . Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Bar-On, Yinon M.; Phillips, Rob; Milo, Ron (17 May 2022). "The biomass distribution on Globe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (25): 6506–6511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711842115 . ISSN0027-8424. PMC 6016768 . PMID29784790.

- ^ Schwelm A, Badstöber J, Bulman S, Desoignies N, Etemadi M, Falloon RE, Gachon CM, Legreve A, Lukeš J, Merz U, Nenarokova A, Strittmatter 1000, Sullivan BK, Neuhauser South (April 2022). "Not in your usual Height x: protists that infect plants and algae". Molecular Plant Pathology. 19 (4): 1029–1044. doi:10.1111/mpp.12580. PMC 5772912 . PMID29024322.

- ^ Kamoun Due south, Furzer O, Jones JD, Judelson HS, Ali GS, Dalio RJ, Roy SG, Schena L, Zambounis A, Panabières F, Cahill D, Ruocco 1000, Figueiredo A, Chen XR, Hulvey J, Stam R, Lamour Yard, Gijzen M, Tyler BM, Grünwald NJ, Mukhtar MS, Tomé DF, Tör M, Van Den Ackerveken M, McDowell J, Daayf F, Fry WE, Lindqvist-Kreuze H, Meijer HJ, Petre B, Ristaino J, Yoshida K, Birch PR, Govers F (May 2015). "The Top 10 oomycete pathogens in molecular establish pathology". Molecular Plant Pathology. xvi (4): 413–34. doi:10.1111/mpp.12190. PMC 6638381 . PMID25178392.

- ^ Campbell, N. and Reese, J. (2008) Biology. Pearson Benjamin Cummings; 8 ed. ISBN0805368442. pp. 583, 588

- ^ Lauckner, 1000. (1980). "Diseases of protozoa". In: Diseases of Marine Animals. Kinne, O. (ed.). Vol. ane, p. 84, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK.

- ^ Cox, F.E.G. (1991). "Systematics of parasitic protozoa". In: Kreier, J.P. & J. R. Baker (ed.). Parasitic Protozoa, 2d ed., vol. i. San Diego: Academic Press.

- ^ Keen EC (July 2013). "Beyond phage therapy: virotherapy of protozoal diseases". Future Microbiology. 8 (7): 821–3. doi:10.2217/FMB.xiii.48. PMID23841627.

- ^ Hyman P, Atterbury R, Barrow P (May 2013). "Fleas and smaller fleas: virotherapy for parasite infections". Trends in Microbiology. 21 (5): 215–220. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2013.02.006. PMID23540830.

- ^ Liu YJ, Hodson MC, Hall BD (September 2006). "Loss of the flagellum happened only in one case in the fungal lineage: phylogenetic structure of kingdom Fungi inferred from RNA polymerase Ii subunit genes". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 6: 74. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-half dozen-74. PMC 1599754 . PMID17010206.

- ^ "ARS Parasite Collections Assist Inquiry and Diagnoses". USDA Agricultural Research Service. January 28, 2010.

- ^ Durham, Sharon (Jan 28, 2010) ARS Parasite Collections Assist Inquiry and Diagnoses. Ars.usda.gov. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Introduction to the Apicomplexa. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Fossil Record of the Ciliata. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Klebsormidiales. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-twenty.

- ^ Introduction to the Choanoflagellata. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Introduction to the Oomycota. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Introduction to the Phaeophyta Archived 2008-12-21 at the Wayback Machine. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Introduction to the Xanthophyta. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Introduction to the Basal Eukaryotes. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Why Is The Museum On The Web?. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-xx.

- ^ Fossil Record of Diatoms. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-twenty.

- ^ Introduction to the Chrysophyta. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Introduction to the Prymnesiophyta. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Fossil Record of the Dinoflagellata. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Systematics of the "Green Algae", Part i. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Fossil Tape of the Rhodophyta. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Fossil Record of the Radiolaria. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Fossil Record of Foraminifera. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Introduction to the Testaceafilosea. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Fossil Record of the Eukaryota. Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-xx.

Bibliography [ edit ]

General [ edit ]

- Haeckel, East. Das Protistenreich . Leipzig, 1878.

- Hausmann, Yard., Due north. Hulsmann, R. Radek. Protistology. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchshandlung, Stuttgart, 2003.

- Margulis, Fifty., J.O. Corliss, Grand. Melkonian, D.J. Chapman. Handbook of Protoctista. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Boston, 1990.

- Margulis, Fifty., One thousand.V. Schwartz. Five Kingdoms: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth, 3rd ed. New York: Westward.H. Freeman, 1998.

- Margulis, L., L. Olendzenski, H.I. McKhann. Illustrated Glossary of the Protoctista, 1993.

- Margulis, L., Thou.J. Chapman. Kingdoms and Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth. Amsterdam: Bookish Press/Elsevier, 2009.

- Schaechter, M. Eukaryotic microbes. Amsterdam, Academic Press, 2012.

Physiology, ecology and paleontology [ edit ]

- Foissner, Due west.; D.Fifty. Hawksworth. Protist Diversity and Geographical Distribution. Dordrecht: Springer, 2009

- Fontaneto, D. Biogeography of Microscopic Organisms. Is Everything Modest Everywhere? Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2011.

- Levandowsky, Chiliad. Physiological Adaptations of Protists. In: Jail cell physiology sourcebook : essentials of membrane biophysics. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier/AP, 2012.

- Moore, R. C., and other editors. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology . Protista, part B (vol. i [ permanent expressionless link ] , Charophyta, vol. 2, Chrysomonadida, Coccolithophorida, Charophyta, Diatomacea & Pyrrhophyta), part C (Sarcodina, Chiefly "Thecamoebians" and Foraminiferida) and function D [ permanent dead link ] (Importantly Radiolaria and Tintinnina). Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America; & Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press.

External links [ edit ]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Protista . |

- Tree of Life: Eukaryotes

- A coffee applet for exploring the new college level classification of eukaryotes

- Plankton Chronicles – Protists – Cells in the Sea – video

- Holt, Jack R. and Carlos A. Iudica. (2013). Diversity of Life. http://comenius.susqu.edu/biol/202/Taxa.htm. Final modified: 11/18/13.

- Tsukii, Y. (1996). Protist Information Server (database of protist images). Laboratory of Biology, Hosei University.[one]. Updated: March 22, 2016.

Animal-like Protists Are Commonly Called Algae

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protist

Komentar

Posting Komentar